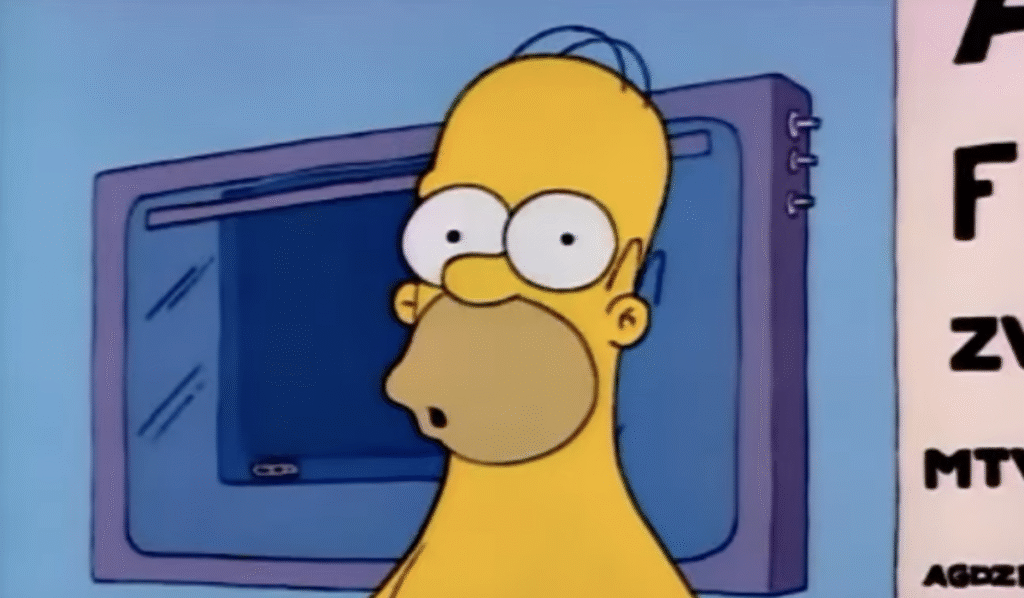

Homer J. Simpson, where the “J” stands for Jay, or possibly for “Just trust me on this”, is one of the most recognizable figures in the history of television. Yes, more recognizable than Tony Soprano discussing gabagool with his ducks, more ubiquitous than the foul-mouthed children of South Park, more ingrained than Seinfeld’s East Coast etiquette seminars disguised as sitcoms, and perhaps even more instantly legible than Captain T. Kirk barking orders from the bridge of the Enterprise. Homer Simpson is not merely a character, but rather he is a shared cultural reflex. You see the silhouette everywhere. Two hairs, a donut-shaped head, a posture permanently leaning toward the nearest snack, and your brain fills in the rest before your heart has time to object.

It is with Homer Simpson that America, no, the world, learned to love an eccentric bald man in a white polo shirt who chokes his own son, fears vegetables, and considers “trying” to be the first step toward failure. And yet, it is also with Homer Simpson that every other television character falls just a little short. Because Homer is not simply funny or quotable or endlessly meme-able, he is the epitome of the deeply flawed but fundamentally good human being. He represents humanity with its warts and all. And humanity, if we’re being honest, has plenty of warts.

Yes, humankind has a long résumé of historical blemishes and violent outbursts, but it is also responsible for astonishing kindness, improbable forgiveness, and the kind of forward thinking that occasionally nudges the species toward something resembling progress. Homer Simpson somehow contains all of this. He is us. He is every diabolical vice we pretend we’ve conquered, every decadent addiction we swear we’re cutting back on Monday, and every flash of anger we keep dormant until traffic or the internet wakes it up. He is every emotional outburst we bottle up until it explodes at precisely the wrong moment, and every sentimental scrap of love we share with our families, our friends, and, when no one is looking, ourselves.

This is a lot to ask of a cartoon character who once tried to build a barbecue pit and ended up in the emergency room. But Homer is larger than life, both physically and metaphorically. He is comedy and tragedy operating in the same body, often within seconds of each other. He is the everyman, but he is also a prototype of an oddly instructive model of what humans are and, in quieter moments, what they might even aspire to be. He is, essentially, every red-blooded blue-collar American distilled into one animated figure who believes that alcohol is both the cause of and solution to all of life’s problems.

Matt Groening created Homer while waiting outside James L. Brooks’s office, sketching and killing time the way creative people often do before history accidentally happens. The Simpsons first appeared as shorts on The Tracey Ullman Show in 1987, and quickly evolved into something far bigger than anyone could reasonably predict. By December of 1989, just a few days before Christmas, the family landed their own show titled The Simpsons. The debut episode revolved around Homer saving money all year for Christmas, only to lose the last of it at the dog track after Bart needed a tattoo removed. It is a very Homer problem. It has noble intentions undermined by impulsive decisions and compounded by bad luck. But Homer comes home not empty-handed exactly. Instead, he brings a dog that came in last place. That dog, Santa’s Little Helper, saves Christmas in the only way The Simpsons ever really saves anything. Emotionally, imperfectly, and at the last possible second.

Santa’s Little Helper is still around today, at least in television form, as The Simpsons barrels forward with thirty-seven seasons, more than eight hundred episodes, and additional seasons already promised, like renewals from a benevolent god who refuses to let Springfield die. It is the longest-running television series in history, with another feature film looming on the horizon. But the true anomaly isn’t the show’s longevity. It’s Homer.

Most great characters have layers. Even cartoon characters have layers. But Homer possesses a kind of emotional depth that sneaks up on you. On the surface, he is a lazy gorilla of a man. He is apparently dumb, intellectually incurious, and frequently feral. He is often portrayed as the worst version of ourselves. Homer is a barely contained animal in clothes. But underneath the donut crumbs and beer foam is a mind that operates with a strange, almost alarming efficiency. Homer may work as a low-level employee at a nuclear power plant, a fact that remains unsettling, but he brings home enough money to support a family of five, two pets, a house, two cars, and a rotating list of extracurricular disasters. He even finds time to drink at Moe’s, which is either a testament to his time management skills or a warning sign we’ve all agreed to ignore.

What makes Homer extraordinary isn’t his résumé though. It’s his resilience. Homer rises to occasions most of us would avoid entirely. He barrels headfirst into opportunities that should terrify him, emotionally and physically, and somehow emerges intact. He can experience a full spectrum of emotional turmoil in seconds and come out the other side ready to move forward without ruminating, spiraling, or starting a therapeutic podcast about it. This, in essence, is what makes Homer tick. He has mastered emotional connection and intelligence while disguised as a cartoon man-ape who loves donuts.

A perfect example arrives in the Season Two episode “One Fish, Two Fish, Blowfish, Blue Fish.” Homer eats poisoned blowfish at a sushi restaurant and is told by Dr. Hibbert that he has twenty-four hours to live. Sitting in his underwear on an exam table, Homer is informed he will experience the five stages of grief, which are denial, anger, fear, bargaining, and acceptance. He processes all five almost immediately. It’s a blink-and-you-miss-it moment of emotional genius, so efficient it astonishes Dr. Hibbert himself. And then Homer moves on, because that’s what he does.

Homer may be quick to anger and quicker to strangle Bart, but he is just as quick to forgive, forget, and move forward. Women throw themselves at him, and he remains loyal to Marge, who loves him with a devotion that defies logic and physics. He endangers himself repeatedly for his family, whether by becoming a human cannonball, a baseball mascot, or something worse that hasn’t been medically classified yet. He saves Springfield from nuclear annihilation, travels to space, trips acid with Johnny Cash, forgives his mother for abandoning him twice, and still hosts his sisters-in-law, which may be his greatest act of heroism.

Homer Simpson is simple and complex all at once. He loves television. He eats everything in sight. He dreams of peace and quiet in an inflatable kiddie pool, chewing on a hot dog that may or may not belong to him anymore. But he also shows up. Every time. When called upon, Homer answers. He is the head of the greatest family in television history and remains, improbably, its emotional center.

Homer J. Simpson is a one-of-a-kind creation. He’s a legend not because he is perfect, but because he is loudly, messily, and unapologetically so…human.